- a medium of exchange

- a measure of value, or unit of accounting

- a standard of deferred payment

- a store of value

Here's an article at theatlantic.com siding with Bernanke regarding his claim that gold isn't money. The writer repeats Bernanke's comment that gold is an asset, but goes on to say that gold isn't a well-accepted medium of exchange, even if it's accepted as such in some locations —

http://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2011/07/bernanke-to-ron-paul-gold-isnt-money/241903/

The writer goes on to say that gold was once money, and could be again, if the U.S. were to re-adopt a gold standard —Gold Isn't a Well-Accepted Medium of Exchange

So what is money? It's a commonly circulated medium of exchange. Let's test this with an example. Is an iPad money? Of course not: if you go to the grocery store and hope to buy $500 worth of groceries, unless you get a very strange cashier, the store won't accept your iPad in exchange. If you provide $500 worth of gold, you would see the same result: a sale would not occur. Some people in some places might accept gold as a means of exchange, but that can be true for other things that we wouldn't consider money either.

The comment that gold could be money again implies that something functioning as money depends on a particular nation deciding to use it as the standard for it's currency. But notice that whether or not a particular nation decides to adopt a gold standard, has no effect on whether or not gold can serve the four functions of money. That a particular government doesn't use gold as its currency standard, doesn't make gold less effective as a store of value, or a medium of exchange, for example — even if people subject to that government are less inclined to trade with gold (or any other commodity) as a result of it not being the standard.So perhaps Paul would have been a little more satisfied with Bernanke's response if he said. "No, but it could be." As a matter of fact, gold was once money and could be again if the U.S. re-adopts the gold standard. But at this time, gold is not money.

And using the iPad example the writer gave, notice that iPads wouldn't function well as money, even if governments adopted an 'iPad standard' for their currencies, because iPads don't serve the required functions of money: 1) iPads are expensive, and aren't divisible, so they wouldn't function well as a medium of exchange, 2) iPads could serve as a unit of accounting, though they wouldn't work well here either because of their price relative to many other cheaper goods, 3) but because iPads go obsolete so quickly, they would be useless as a standard of deferred payment, 4) and even if they went obsolete more slowly, they can also decay in storage, so they are not useful as a store of value.

Unlike iPads and many other commodities, gold has all the properties required by money. And notice that as a store of value, gold is more properly defined as money than the U.S. dollar, since over the long term the U.S. dollar is a wasting asset — it tends to lose value every year.

It's not surprising that this would be the case, since gold is rare, and humans can't simply make or mine as much as they want — if this weren't so, gold would be worthless. For the U.S. dollar, or any other fiat currency, exactly the opposite is true — the intrinsic value of the currency is kept as close to zero as possible, to minimize the cost of producing it.

The graph below shows world gold production from 1900 through 2012. In 2012 world gold production was just above 2,600 metric tons per year (2,600,000 kilograms, or 5,732,018.82 pounds) --

http://minerals.usgs.gov/minerals/pubs/commodity/gold/

https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/gold-production?time=1900..latest

So how much total gold is above ground? No one knows, but in 2013, estimates for the total amount of gold mined since the dawn of time were around 170,000 metric tons.

Here's the estimate from the 'World Gold Council' --

http://www.gold.org/supply-and-demand/supply

At the end of 2013, there were 177,200 tonnes of stocks in existence above ground. If every single ounce of this gold were placed next to each other, the resulting cube of pure gold would only measure 21 metres in any direction. While its rarity endures, the sources of gold have become as geographically-diverse as gold demand.

The 'Gold Money Foundation' has a paper explaining why the 'World Gold Council' estimate could overstate the total gold supply by about 16,000 metric tons, as of 2011 --

https://wealth.goldmoney.com/images/media/Files/GMYF/theabovegroundgoldstock.pdf

So using the 2012 gold production figure of 2,600 metric tons, the total world gold stock grew by about 1.5 to 1.6%, depending on the initial estimate used for the total stock. According to the 'Gold Money Foundation', the long term average increase in the total world gold stock is about 2% annually --

https://wealth.goldmoney.com/images/media/Files/GMYF/theabovegroundgoldstock.pdf

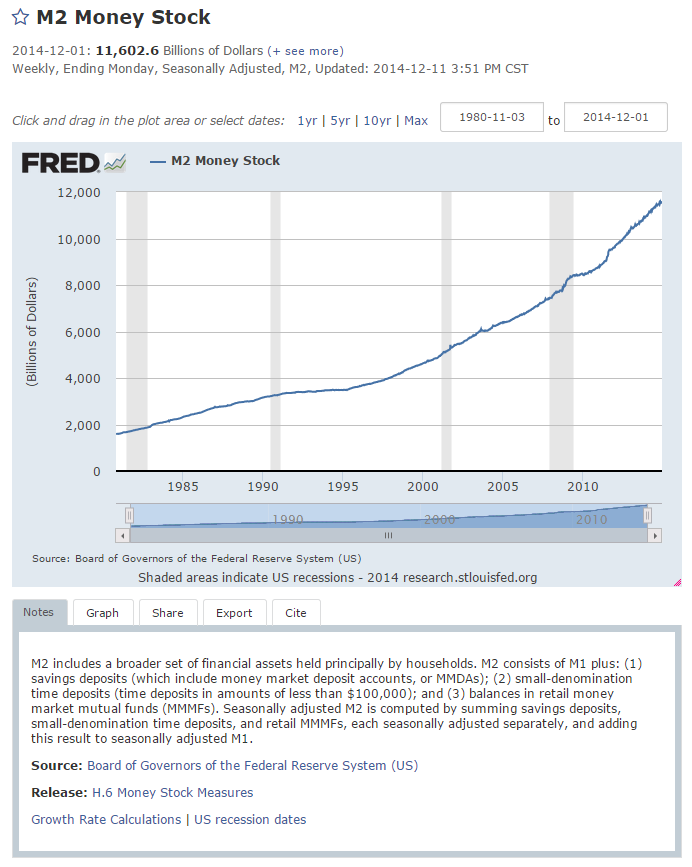

For comparison, consider the chart below from the 'Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis', showing the M2 Money Stock from 1980 through 2014. Roughly speaking, M2 money includes various types of savings deposits, along with M1 money, and M1 money includes the currency in circulation and checking account deposits. Notice that over those 34 years, the M2 Money Stock twice doubled, with a total increase of roughly seven fold, while the world gold stock increased by approximately 65% (again, depending on the gold stock estimates used) --

http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/series/M2/

Now consider this absurd quote from John Maynard Keynes, in his 'General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money' (see Chapter 10, part VI), where he attempts to make gold mining sound no more sensible than having the Treasury bury bank-notes for people to dig up. Notice that Keynes describes this as 'better than nothing' as an economic stimulus, even though he considered it a poor choice (it's much worse than he thought) --

https://www.hetwebsite.net/het/texts/keynes/gt/chap10.htm

It is curious how common sense, wriggling for an escape from absurd conclusions, has been apt to reach a preference for wholly 'wasteful' forms of loan expenditure rather than for partly wasteful forms, which, because they are not wholly wasteful, tend to be judged on strict 'business' principles. For example, unemployment relief financed by loans is more readily accepted than the financing of improvements at a charge below the current rate of interest; whilst the form of digging holes in the ground known as gold-mining, which not only adds nothing whatever to the real wealth of the world but involves the disutility of labour, is the most acceptable of all solutions.

If the Treasury were to fill old bottles with bank-notes, bury them at suitable depths in disused coalmines which are then filled up to the surface with town rubbish, and leave it to private enterprise on well-tried principles of laissez-faire to dig the notes up again (the right to do so being obtained, of course, by tendering for leases of the note-bearing territory), there need be no more unemployment and, with the help of the repercussions, the real income of the community, and its capital wealth also, would probably become a good deal greater than it actually is. It would, indeed, be more sensible to build houses and the like; but if there are political and practical difficulties in the way of this, the above would be better than nothing.

Of course, this is ridiculous — as a productive endeavor, gold mining is useless, but as a means to extract a form of money that can actually store value, gold mining has been wildly successful.

Mining gold is useful precisely because it's hard — because gold is scarce, and because men have no direct control over its supply, except through long hours of hard work.

If gold were common and easy to produce, like a bank-note printed by the Treasury, it would be no more useful as a form of money than a bank-note, and no one would have any incentive to mine it.

Here's a chart from Jeremy Seigel's, 'Stocks for the Long Run', to demonstrate how badly the U.S. dollar serves as a store of value. And note that the U.S. dollar is the world's reserve currency, so among the world's fiat currencies, the U.S. dollar is held in the highest confidence --

http://www.aaii.com/journal/article/real-returns-favor-holding-stocks.touch

Here's a question for those who, like Keynes, think gold mining is ridiculous —

If you could print $100 bills in your home, knowing you would be safe from prosecution for doing so, whether it was legal or not, would you?If you answered that question honestly, you have a deep understanding of why fiat currencies tend to decline in value and why men are compelled to mine gold — you understand why even holding the world's reserve currency is a large negative return over time.

The irony of the disparaging quote above regarding gold mining from 'The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money', and Keynesianism in general, is that they have contributed to conditions that make gold mining more necessary than ever — that is, if societies want some form of money that stores value.

No comments:

Post a Comment