If you thank that is an exaggeration, watch Krugman in this interview from August, 2011, where he parrots Keynes in supporting government stimulus spending, with his explicit statement that the spending be on something that wastes resources and helps no one — that is, a military buildup for a fictitious alien invasion --

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nhMAV9VLvHA

http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/05/09/the-moral-equivalent-of-space-aliens/

If we discovered that, you know, space aliens were planning to attack and we needed a massive buildup to counter the space alien threat and really inflation and budget deficits took secondary place to that, this slump would be over in 18 months. And then if we discovered, oops, we made a mistake, there aren’t any aliens, we’d be better [off].

Paul Krugman's blog is dominated by content like the statement quoted above, which makes it little more than an endless stream of fallacies. Here is another typical example, from a Krugman post in February, 2015, where Krugman attempts to dismiss concerns about the mounting U.S. public debt --

http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2015/02/06/debt-is-money-we-owe-to-ourselves/

Debt Is Money We Owe To Ourselves

Paul Krugman FEBRUARY 6, 2015 7:32 AM

Antonio Fatas, commenting on recent work on deleveraging or the lack thereof, emphasizes one of my favorite points: no, debt does not mean that we’re stealing from future generations. Globally, and for the most part even within countries, a rise in debt isn’t an indication that we’re living beyond our means, because as Fatas puts it, one person’s debt is another person’s asset; or as I equivalently put it, debt is money we owe to ourselves — an obviously true statement that, I have discovered, has the power to induce blinding rage in many people.

Think about the history shown in the chart above. Britain did not emerge impoverished from the Napoleonic Wars; the government ended up with a lot of debt, but the counterpart of this debt was that the British propertied classes owned a lot of consols.

More than that, as Fatas points out, rising debt could be a good sign. Think of my little two-classes model of debt, where some people are less patient than others — perhaps (to step outside the model a bit) because they have better investment opportunities. Moving from a very limited financial system that doesn’t allow much debt to a somewhat more open-minded system should, in that case, be good for growth and welfare.

The problem with private debt is that we have good reason to believe that in very wide-open financial systems people get irrationally exuberant, lending and borrowing to an extent that they eventually realize was excessive — and that there are huge negative externalities when everyone tries to deleverage at once. This is a very big problem, but it’s not about generalized excess consumption.

And the problems with public debt are also mainly about possible instability rather than “borrowing from our children”. The rhetoric of fiscal debates has been, for the most part, nonsense.

Think about the history shown in the chart above. Britain did not emerge impoverished from the Napoleonic Wars; the government ended up with a lot of debt, but the counterpart of this debt was that the British propertied classes owned a lot of consols.

More than that, as Fatas points out, rising debt could be a good sign. Think of my little two-classes model of debt, where some people are less patient than others — perhaps (to step outside the model a bit) because they have better investment opportunities. Moving from a very limited financial system that doesn’t allow much debt to a somewhat more open-minded system should, in that case, be good for growth and welfare.

The problem with private debt is that we have good reason to believe that in very wide-open financial systems people get irrationally exuberant, lending and borrowing to an extent that they eventually realize was excessive — and that there are huge negative externalities when everyone tries to deleverage at once. This is a very big problem, but it’s not about generalized excess consumption.

And the problems with public debt are also mainly about possible instability rather than “borrowing from our children”. The rhetoric of fiscal debates has been, for the most part, nonsense.

Krugman's blog post quoted above hardly deserves comment — since it is so poorly written, the fallacies it contains should be obvious to almost anyone.

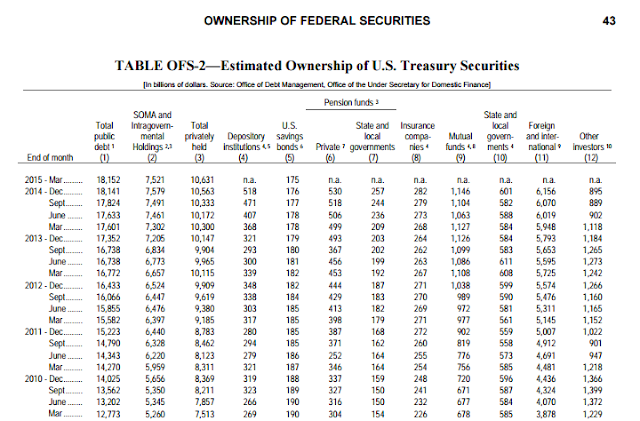

First, the title is obviously false — it is true that the largest portion of the U.S. public debt is held by government agencies (mainly Social Security), but a large portion of the U.S. debt is held by foreign nations. Here is part of a table from the U.S. Treasury's June 2015 Bulletin, showing the estimated ownership of U.S. Treasury Securities, from 2010 through March 2015. Notice that this table shows that 'foreign and international' owners (column 11) were holding about 34% of the total U.S. public debt in December of 2104 --

https://www.fiscal.treasury.gov/files/reports-statements/treasury-bulletin/b2015-2.pdf (p. 43)

https://web.archive.org/web/.../https://www.fiscal.treasury.gov/files/reports-statements/treasury-bulletin/b2015-2.pdf

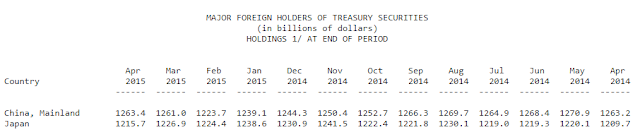

And notice that China and Japan alone were holding over 13% of the U.S. public debt in March of 2015 --

http://ticdata.treasury.gov/Publish/mfh.txt

But regardless of the breakdown of the ownership of the U.S. public debt, Krugman's statement that 'debt is money we owe to ourselves — an obviously true statement', is, rather, an obviously false statement. There is nothing about government debt in general that entails 'taxpayers owing it to themselves'. At a minimum, this would mean that all government debt securities are purchased by the government with tax revenue. This was never true, and it certainly is not true now.

But even more importantly, notice that even in the case of the Social Security Administration's past purchase of government treasuries with surplus payroll deductions — as an example of 'owing it to ourselves' — we do not 'owe it to ourselves', since current beneficiaries of government programs like Social Security and Medicare will not pay, nor will they even suffer any consequences of, the growing debt that is being generated in part to pay for their benefits — obviously, future taxpayers will, since current taxpayers will not live long enough.

So even under the assumption that the phrase 'owing it to ourselves' is simply meant to indicate government debt that was purchased with tax revenue, and so is held by government agencies (i.e. debt owned by U.S. taxpayers), that debt will still affect future taxpayers more than current taxpayers (especially given future interest rate increases). In short, Krugman's phrase — 'debt is money we owe to ourselves' — is a euphemism to disguise the unequal impacts of the debt between current and future taxpayers.

So how is it possible to justify Krugman's claim: 'no, debt does not mean that we’re stealing from future generations', when we know that the growing debt is certainly not helping future generations?

But what is truly perversely fascinating in this nonsensical 'we owe money to ourselves' talk, is that anyone would take this seriously — never mind a Nobel laureate economist.

I wrote about the absurdity of pretending you owe yourself money last year in this post —

http://maxautonomy.blogspot.com/2014/06/pretending-you-owe-yourself-hazard.html

In Krugman's blog post quoted above, he mentions that one person's debt is another person's asset — yes, but this is only true if there really are two different people. Your debt is not also your asset. So making the claim that your debt is your largest asset, is exactly the same as saying 'I'm broke'. All debt is a claim against future earnings, and government debt is a claim on the future earnings of taxpayers, regardless of the owner of that government debt. This is what makes the commonly heard comment that the Social Security 'trust fund' pays benefits so absurd — all the government 'trusts' that hold U.S. Treasuries are simply promises to collect future taxes (i.e. they are claims on future tax receipts), and so future taxpayers must pay, if those securities are ever to be redeemed in order to pay some government expense, like Social Security or Medicare benefit payments.

It is hard to believe that it is not obvious to people that they cannot also treat their debt as an asset, and that it should require an explanation as to why, but it must, since it is repeated ad nauseam — even by a Nobel laureate.

Making the claim that we 'owe it to ourselves' does nothing to mitigate a debt problem. The U.S. government 'trust funds' are an unfunded liability of U.S. taxpayers — that is, they are promises to collect payments from future taxpayers. And notice that this simple fact — which is determined by the U.S. Treasury securities held by the trusts (that's just how they work) — stands in direct contradiction to Krugman's claim that 'debt does not mean that we’re stealing from future generations'. The larger the U.S. debt grows — including the so-called 'trusts' — the larger the burden that will be borne by future taxpayers.

Here are more details on how the government trusts are a liability to U.S. taxpayers. If you are a U.S. taxpayer, you pay for the U.S. trust funds, they do not pay for you —

http://maxautonomy.blogspot.com/2015/05/the-trust-fund-tolls-for-thee.html

And notice the glaring contradiction in Krugman's comment that private lenders alone have a tendency to become 'irrationally exuberant'. I suppose this is his shorthand code to readers who wish to pretend that government requirements had nothing to do with the financial crisis of the Great Recession. This notion that governments are consistently rational and responsible, in contrast to the private sector, is so utterly ridiculous there is no reason to comment on it. Anyone who responds affirmatively to such a comment is simply expressing a blindness driven by a biased agenda. The crises, strife, and misery, caused directly by the world's governments are too widely well known to be worthy of mention.

To those who would now launch into a diatribe about the obvious harm that has been caused by private companies (no argument here), I would only say that your moral compass and your ability to measure harm are a bit off. Good luck.

Of course, this is consistent with Krugman's mantra that all government spending has some magical ability to create well being, whereas private sector spending or saving does not. That Krugman would be comfortable in repeating such a ridiculous claim, as well as 'Debt Is Money We Owe To Ourselves', is a testament to how insulated he is from any real criticism.

So much for the Nobel prize.

No comments:

Post a Comment